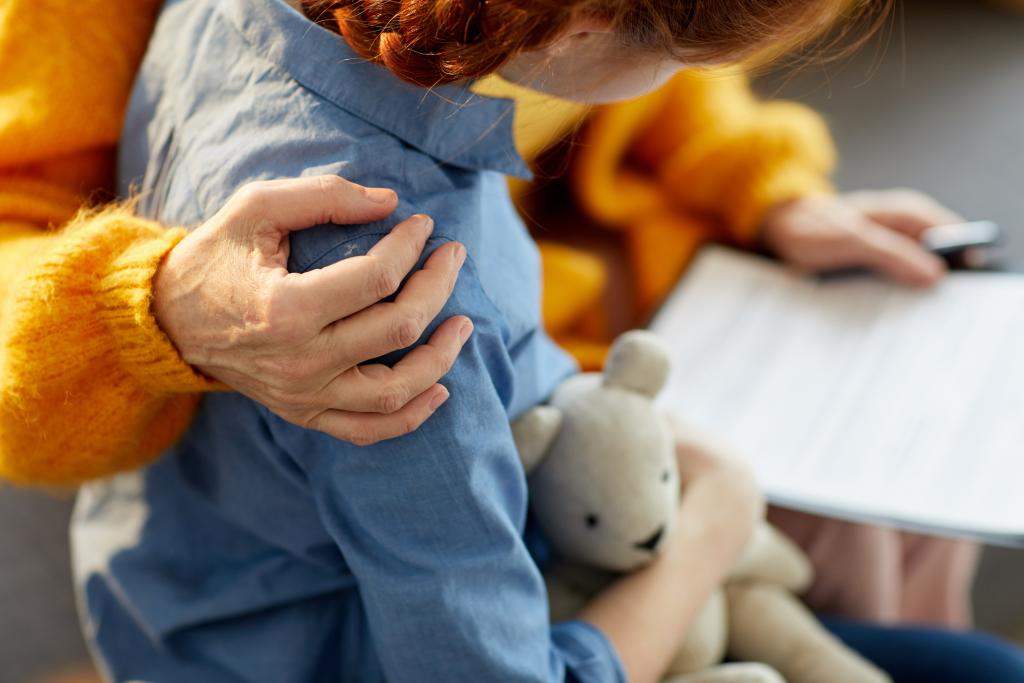

Divorce is not only the end of a relationship between two adults, but also a major change in a child’s world. Research shows that what matters most is not the separation itself but how children are supported through the changes that follow (Amato, 2010).

With over 25 years’ experience working with children and families – including 18 years at Cafcass – I have seen first-hand how separation can be managed in a way that protects children or unfold in ways that leave lasting emotional scars. The difference lies in whether parents manage their own hurt and keep their children’s emotional needs at the heart of the process.

How Children Experience Divorce

Children may react with sadness, confusion, anger, or fear. Fear often being the most dominant feeling – fear of abandonment, loss of love, conflict, or major changes such as moving house or school.

Raised voices can feel extremely frightening, and when conflict is frequent, a volatile atmosphere can be deeply unsettling for a child.

Children may also feel torn between divided loyalties, worried that showing love to one parent may somehow hurt the other, that loving one parent might hurt the other.

These difficult experiences can show up in many ways, including behavioural changes, sleep problems, or difficulties at school.

What Children Need Most

Above all, children need honesty and reassurance. They benefit from age-appropriate explanations and frequent reminders that the separation is not their fault and that both parents still love them.

Although parents know children should not be caught in conflict, strong emotions can cloud judgement. Shielding children from hostility and involving both parents in their lives is critical. Love and reassurance could also come from extended family and friends. Grandparents, siblings, cousins, and peers provide stability, helping children feel connected and “normal” during uncertain times.

Safe spaces where children can express feelings of sadness, anger, or confusion are essential. While friends and family may offer this, schools can also play a key role by providing a neutral and professional environment.

Predictable routines such as school, mealtimes, extracurricular activities and bedtimes bring comfort when other areas of life feel unstable.

When Things Go Wrong

Exposure to high conflict, disrupted contact, or prolonged uncertainty can have long-lasting effects. Some children internalise distress, showing anxiety or depression, while others act out through aggression or withdrawal. Research shows that unresolved parental conflict increases the likelihood of children struggling in their own adult relationships, sometimes leading to difficulties with trust, stability, and commitment.

Thoughts for Parents

What protects children most during separation is not avoiding change, but ensuring they feel safe, loved, and heard. While parents cannot control every outcome, they can influence the environment in which their child grows up.

Children cope best when routines remain stable, when they are shielded from adult conflict, and when they are consistently reassured of their parents’ love. Supporting wider family and peer connections provides an additional sense of stability and belonging. Equally important is giving children permission to express feelings at their own pace, without pressure to “be strong” or take sides.

When parents take care of their own well-being and communicate respectfully, they create space for children to adapt without carrying adult burdens. Ultimately, while going through a divorce is a temporary chapter, the journey of parenthood is lifelong. By keeping children out of conflict, protecting routines, and surrounding them with love, parents give their children the best chance not only to cope but to grow into resilient, secure adults.

Article written by Pauline Newell, Independent Social Worker and Safeguarding Consultant.

Contact: Pauline Newell | LinkedIn